Tagliatelle al Ragù alla Bolognese [Fresh Egg Pasta Ribbons with Meat Sauce in the style of Bologna] was our most popular pasta dish at Bellavitae. It appeared on the menu when we opened the brick oven every autumn, and lasted into the cold winter months when the oven’s open fire was roaring to keep everything in the restaurant toasty. There is nothing more satisfying in the dead of winter than a comforting bowl of homemade egg pasta with beef ragù.

Ragù alla Bolognese is a centuries-old recipe, where beef is combined with a perfect balance of chopped vegetables and left to sputter for hours over low heat, rendering it succulent and deeply flavored. I know of nothing that so easily warms the soul.

This ragù is very easy to make; the only challenge is that of time. It freezes beautifully or you can hold it in the refrigerator for at least three days. Ours is a most authentic recipe and once you try it you’ll understand why any imitation or variation (some say bastardization) is simply not acceptable – and why the original became so famous.

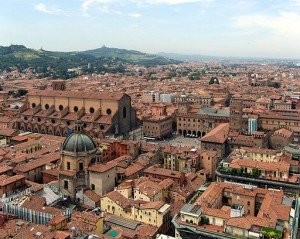

Emilia-Romagna – The Richest Gastronomic Region in Italy

Ragù alla Bolognese traces its beginnings to Bologna, where Europe’s first law university was founded in 1119; hence the city’s nickname La Dotta [the Learned]. Bologna lies in the middle of Emilia-Romagna, through which three ancient throughways converge: The via Romanea Francigena, the via Pedemontana, and the via Emilia. Throughout history these roads attracted settlers and rulers from afar – Etruscans, Romans, Lombards, and Byzantines; pilgrims from the north, the Farnese from Rome; and Bourbons from Naples and Austria. During the 16th Century, Pope Paul III established his nephew in Parma and the region became the site of frequent ceremonial visits that included banquets and festivities overseen by cooks of international reputation.

.

The land of Emilia-Romagna is well-suited to cultivation, and the region is a great producer of tomatoes, sugar beets, peas, and beans. But the region is best known for its famous cured pork – the prosciutto of Parma and culatello of Zibello. The most renowned aged cheese on earth, of course, is Parmigiano-Reggiano. And the world’s most luxurious vinegar comes from Modena – balsamico [balsamic]. This abundance of gastronomic delights has earned Bologna its other Italian nickname: La Grassa [the Fat]. Pavel Muratov, the Russian art historian explains:

“In Bologna there is something light that cheers the eye, agreeably not too complicated. It is a city of contented, healthy people. The fattest granaries [grain storehouses] and vineyards of Italy surround it, producing a renowned wine. No other place can compare with Bologna for the abundance, variety, and good price of every possible and imaginable foodstuff, and it is no accident that the Italians call it ‘Bologna la Grassa.’”

.

The History of Ragù alla Bolognese

Ragù in Emilia-Romagna has been traced back to the 16th century, when it was enjoyed by wealthy courts of noble families. The origins are related to the French ragôut, a noun derived from the verb ragôuter, which means to “wake up”, “whet the appetite”, or “give more taste”. Ragôut, of course, is a hearty French stew of meat, fish, game, or vegetables, cut into small pieces and cooked very slowly in some fat over low heat.

Ragù alla Bolognese has evolved – like all classic dishes – not just over decades or generations, but over the centuries. For example, original versions of the dish didn’t include tomatoes. Tomatoes weren’t known or used in Italy until later in the 16th century. Pork is included in some recipes, but the common usage of it likely occurred after World War II, when the meat became more affordable. Likewise, butter was likely a latter addition. There are no herbs or spices in Ragù alla Bolognese (and certainly never garlic!), although you frequently see the addition of Bay leaves.

The Accademia Italiana della Cucina [Italian Academy of Cuisine] was formed in 1953 to record and declare official the classic recipes of regional Italian cooking. In its encyclopedia of over 2,000 dishes is Ragù alla Bolognese. The challenge of reducing a classic recipe to one official version is exceedingly difficult. Can you imagine if someone asked you to describe the authentic recipe for American fried chicken? Or apple pie? It’s no wonder the Accademia took 38 years to agree on the official recipe for Ragù alla Bolognese. There are many recipes for the dish in and around Bologna. Ask ten different cooks in the area what the authentic recipe is and you’ll get ten different answers – all of them, of course, are authentic.

.

Bellavitae’s Recipe

We base our recipe largely on that of the Simili sisters, who have published three Italian cookbooks (alas, none has been translated into English). They began working at the family bakery, located in Bologna, in 1946. Stefano Bonilli, the Bolognese-born director and founder of Gambero Rosso, had this to say about the bakery:

“More than a business, the bakery that the Simili Sisters ran in Via San Felice and then in Via Frassinago was a meeting point for all of Bologna’s gourmets.”

In 1986 the sisters held cooking courses at the Hotel Milano Excelsior di Bologna and three years later they opened the Scuola di Cucina della Sorelle Simili [The Simili Sisters’ School of Cooking], which acquired worldwide acclaim. The school was closed during the summer of 2001.

.

Ragù alla Bolognese Dishes

The most popular dishes that use this ragù include:

- Fresh egg pasta

- The most perfect is, of course, Tagliatelle

- Tortellini is also well-suited

- Dried pasta

- Rigatoni

- Conchiglie

- Fusilli

- With all due respect to my friends in the United Kingdom, spaghetti is not appropriate with this meat sauce!

- Lasagne Verdi al Forno [Baked Spinach Lasagne]

- Polenta alla Bolognese [Baked Polenta with Bolognese Meat Sauce]

- Crespelle alla Bolognese [Italian-style Crêpes with Bolognese Meat Sauce]

- Risotto alla Bolognese [Risotto with Bolognese Meat Sauce]

.

The Ingredients (for six servings)

For the soffritto:

- 3 tablespoons unsalted butter

- 1 tablespoon extra virgin olive oil

- 2 – 3 slices of Prosciutto di Parma or Pancetta, finely chopped (approx 3 oz)

- 1 small yellow onion, peeled and finely chopped

- 2 ribs celery, finely chopped

- 2 – 3 Bay leaves – optional

- 2 carrots, peeled and finely chopped

- 2 chicken livers, finely chopped (approx 3 oz) – optional

.

For the meat sauce:

- 1 ½ lbs ground chuck

- 1 cup milk, hot

- ½ cup dry white wine

- 1 cup brodo di carne [beef broth]

- 1 28-oz can puréed Italian plum tomatoes

- ¼ teaspoon (or to taste) nutmeg, preferably freshly-grated

- Sea salt

- Freshly-ground black pepper

.

A note on the ingredients:

- Butter and olive oil. Use enough to coat the bottom of the skillet, keeping the 3-to-1 ratio

- Bay leaves. Most traditional recipes call for no herbs (or spices or garlic, for that matter), but I like the richness and depth Bay leaves impart in this recipe. I prefer imported Bay leaves to the stronger-flavored and oilier California herb.

Chicken livers. This is marked optional in the recipe, but I would encourage you to use it. After a long braise, the sauce will not take on a chicken liver flavor, but rather will produce an additional layer of flavor complexity, or as some would say, umami. In their classic Italian cookbook, Sfida al Matterello, the Simili sisters, Valeria and Margherita, say this:

Chicken livers. This is marked optional in the recipe, but I would encourage you to use it. After a long braise, the sauce will not take on a chicken liver flavor, but rather will produce an additional layer of flavor complexity, or as some would say, umami. In their classic Italian cookbook, Sfida al Matterello, the Simili sisters, Valeria and Margherita, say this:

“In the past, chicken giblets were included in ragù as well: heart, kidney, and liver; ingredients with a strong flavor that are no longer liked by the modern palate – what a pity! Of these ingredients only the liver has survived; please don’t eliminate it. If you don’t like it, use less, just a half, but include it because in such a small quantity you will not detect it but it really fills out the flavor by giving it more body.”

It should be no surprise that giblets are frequently used in this recipe; it is also common to do so in French ragoûts, such as the financière. It’s usually impossible to buy only two chicken livers at the supermarket, but you can always take the giblets from a whole chicken and freeze them, or alternatively, buy a carton of chicken livers, divide and freeze them in sealable plastic bags.

- Ground Chuck. Use 80 / 20% ground chuck, which will provide the optimum flavor and texture profile for this recipe. Many recipes call for the use of shredded beef, but over the years ground beef has become much more common. For you traditionalists, you can use shredded braised beef. In the recipe registered by the Accademia, thin skirt [cartella] is specified, which is the muscle that separates the lungs from the stomach. However, a more suitable cut is the flank brisket [finta cartella (pancia)], which has more fat and requires longer cooking.

- Milk. Use whole milk for this recipe, not reduced fat or skim. You will be disappointed with the results, otherwise.

- Beef broth. Don’t use beef stock in this recipe. I prefer to use organic beef broth.

- Canned tomatoes. I prefer Italian San Marzano, which have an amazingly fresh flavor. The recipe calls for pureed, but you can use crushed tomatoes, or whole tomatoes and dice them yourself (or run them through a food mill). This is a texture issue – use your personal preference.

.

Preparing Ragù alla Bolognese

For the soffritto:

- Heat the oil and butter in a large, deep, heavy pot over medium heat. When hot, add the chopped onions and prosciutto, sauté until the onions are soft and translucent, but not browned, about five minutes.

- When the onion has clarified, add the celery and Bay leaves. About a minute later, add the carrot and cook for three minutes more, stirring occasionally.

- Meanwhile, clean and prepare the chicken livers. Remove any trace of the bitter-tasting green bile. Crush the livers using the fat end of the knife blade in order to separate the nerve fibers from the flesh. After the nerve fibers have been separated, chop the livers fine.

- Push the soffritto to the perimeter of the pan with a wooden spoon. Place the chopped chicken livers in the center of the pan and cook, flattening and stirring continuously until the meat begins to change color. As it darkens, bring the soffritto back to the middle of the pan and stir everything together for a moment.

.

For the meat sauce:

- Combine the tomatoes and beef broth in a sauce pan and heat over medium heat for later use.

- Separate the ground chuck into thirds. Again, push the soffritto and livers to the perimeter of the pan. Add one third of the ground chuck to the center of the pan and cook, flattening and stirring continuously until the meat begins to change color. While still somewhat pink, push this third of the ground chuck to the perimeter. Repeat this procedure with the second and third portions of the ground chuck. Bring the soffritto back to the middle of the pan and stir everything together for a moment.

- Meanwhile, heat the milk in the microwave or a small saucepan. Don’t let it reach the boiling point, but heat until small bubbles appear around the perimeter of the container.

- Add the hot milk in two or three doses and let it simmer while stirring consistently until it has completely bubbled away, about 10 – 15 minutes. Stir in the nutmeg.

- Bring the meat mixture into the center of the pan, leaving the perimeter clear. Slowly add a third of the wine to the cleared perimeter of the pan. When the wine has fully heated, repeat with the second portion and then the third. Stir the mixture together in the pan and let simmer until the wine has fully evaporated; i.e., when you can no longer detect its aroma, about 10 – 15 minutes.

- Season with salt and freshly-ground pepper.

- Add the hot tomatoes and beef broth.

- After the sauce begins to boil, reduce heat to the laziest of simmers – a bubble or two periodically should reach the surface. Simmer at this temperature with the pot uncovered for at least three hours, stirring occasionally. Taste for salt and pepper, adjust accordingly.

- Combine with the pasta, sprinkle with grated Parmigiano-Reggiano and serve immediately.

.

Tips for Success

- Use gentle heat when preparing the ingredients. Anything over medium will tend to over-brown the surface, which will be magnified after the long simmering.

- Don’t sauté the chicken livers or beef too long or they will dry out. No amount of simmering in the sauce will revive the dried meat.

- If you find the moving of ingredients around in the pot is too burdensome, complete these steps in a separate pan. I do this to save on dishwashing! Just be sure to complete the final simmer in a tall pot in order to reduce evaporation.

- The secret to this ragù is to have an optimal amount of liquid left in the sauce at the end of the long simmering period; i.e., not too runny, but not too dry. Many recipes suggest that if the sauce becomes too dry before its allotted simmering time to add more beef broth. I prefer to simply place a cover on the pot at this point rather than dilute the sauce.

.

Understanding

- Sauté the chicken liver away from the other vegetables because it coagulates immediately when heated. If it touches a hot vegetable, it will cling to it, rather than later dispersing throughout the sauce. Care is taken while separating the livers’ nerve fibers so the ingredient will integrate well with the others.

- Italian cooking utilizes beef broth, which is typically made by braising meat, bones, and vegetables. It is not stock, as is used in French and American cooking. Thus it imparts a softer flavor to dishes, adding hints of flavor, but always taking a back seat to the other ingredients.

- Using a leaner cut of beef will render the sauce less sweet and succulent, creating disappointment in both flavor and texture.

- Salt is added to the meat after it is browned, so as not to encourage release of liquid before it cooks, which would render the meat dry.

- The meat is sautéd briefly only to enhance flavor, it should not be browned. It’s cooked at a relatively low temperature to prevent drying (see Mastering the Techniques of Sautéing and Browning). Once too much liquid is released from the meat, the texture will become rubbery, a process that cannot be reversed.

- Milk is added to the meat before the acidic ingredients (white wine and tomatoes) to protect them from “cooking” the meat and inflicting a inferior texture. The milk also helps to tenderize the meat and adds a sweet, appealing flavor.

- Liquids that are added to the meat are first brought to a hot temperature. Dramatically changing the meat’s temperature by adding cold liquids will alter the proteins’ structure, to the detriment of both flavor and texture.

.

Related:

- Pasta all’Uova Fatta in Casa: The Joy and Satisfaction of Making Homemade Egg Pasta

- The Italian Flavor Base: Battuto, Soffritto, Trito

- Mastering the Techniques of Sautéing and Browning

- Ricette Classiche: Lasagne Verdi al Forno

.

Further Reading:

- The Official Dish of the IDIC 2010: Tagliatelle al ragù Bolognese

- The Italian Academy of Cuisine: La Cucina, The Regional Cooking of Italy

- Official Site: Bologna

- Official Site: Emilia-Romagna

.

how long can sauce be good after open

in the refrigerator?

The sauce should last safely for several days in the refrigerator. After that, I would freeze it. Thaw it in the refrigerator overnight before reheating.