The fundamental essence in many Italian dishes begins with a battuto, soffritto, or trito. These elemental methods in Italian cooking are not afterthoughts or merely decorative, but where Italian flavor begins. To know Italian cooking is to become familiar with these techniques.

A battuto is a flavor base of finely chopped or beaten raw ingredients. The word is a derivative of battere, which means “to strike”, and describes the use of a chef’s knife chopping on a cutting board. A battuto is usually a very finely chopped mixture of lardo (cured pork back fat), salt pork, pork fat, or pancetta with garlic and onions. It can also contain celery, carrots, chilies, and / or other chopped ingredients. Originally, a battuto was parsley and onion chopped in creamed pork lard, but today cooks have substituted olive oil or butter for lard and added other vegetables as well. In Italy, many butchers sell a pre-made basic battuto. Simmered in water, battuto can also serve as an alternative to more expensive meat broth.

Lardo battuto is cured pork fat pounded to a cream with herbs and garlic, used for stuffing or added to a broth or stew at the beginning or end of cooking.

A battuto becomes a soffritto when it is gently sautéed in fat, usually olive oil. A more precise definition of soffritto is a mixture of vegetables – usually onion, celery, carrot, garlic, herbs, and sometimes lardo or pancetta – sautéed in olive oil or butter until they become soft and caramelized, imparting their flavors to any ingredient that follows.

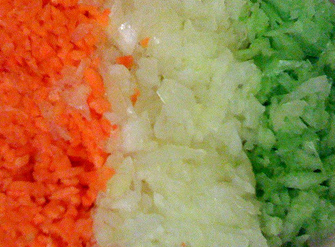

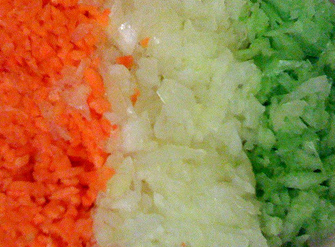

A trito is the same as a battuto but doesn’t contain pork. It’s very finely chopped vegetables, usually including some combination of onions, celery, garlic, carrot, and parsley. Other cuisines use this same technique: refogado in Portuguese, sofrito in Spanish, sofregit in Catalan, mirepoix in French, and “holy trinity” in Creole cooking.

Crudo is a trito of raw vegetables and herbs or other ingredients that are added to a dish or sauce, and then cooked. It can also be a mixture of raw herbs and vegetables that is put directly on (or mixed with) cooked food just before serving, as in Venetian risi e bisi (rice and peas) or pasta primavera.

Italians take their battuti and soffritti very seriously and it’s fair to say that grandma can keep hers a secret. Here are some tips for success:

- While it’s best to hand chop vegetables for soffritto, trito, and crudo, the most effective tool for a battuto is a food processor, using the pulse setting.

- Sauté a soffritto at medium to medium-high heat, no higher. The idea is to impart the ingredients’ flavor into the oil or butter by sautéing them until soft and translucent, but not browned.

- Begin the sauté after the oil becomes hot. In other words, don’t pour the oil in a pan, add the onions, then turn on the heat. Instead, let the pan heat up before adding the oil, then allow the oil become hot before adding ingredients.

- Always begin with the onions and sauté until they clarify. Then add the garlic (if called for), then add the celery, then the carrots. If you sauté the ingredients simultaneously, the intense flavor of the raw, milky onion will be absorbed into the others, rendering them all onions! Moreover, garlic cooks faster than onion and if both are added at the same time, the garlic will become too dark and its pungency will dominate the dish.

- A good rule of thumb for the progression of soffritto ingredients: begin with those that have the strongest flavor and that can withstand the heat the longest; finish with those that are most delicate.

- If your soffritto calls for pancetta, begin the process with the onion and pancetta together.

.

Related: Mastering the Techniques of Sautéing and Browning

.

.