.

Pesto Genovese was one of our most popular signature dishes at Bellavitae. People would travel across town just to experience this simple yet sublime celebration of Italy’s most seductive herb – basil. Guests would frequently ask for the dish in the dead of winter! Of course we would explain that they would need to wait until summer – when basil was at the height of its season – to enjoy the delectable sauce.

Pesto is a centuries-old recipe, where Mediterranean-grown basil is combined with a hint of delicate mountain-grown Vessalico garlic, to which is added Italy’s two most famous aged cheeses – Parmigiano-Reggiano and Pecorino. Add some Italian pine nuts [pinoli] and the cleanest, sweetest sea salt from Cervia. Trickle in the fruitiest, most sublime Taggiasca olive oil and presto! – Pesto Genovese.

So why are we talking about this summer dish in, well, the dead of winter?

Every January 17th — for the last four years — the Virtual Group of Italian Chefs (GVCI) promotes one authentic Italian recipe on its International Day of Italian Cuisines (IDIC). We were honored to participate last year with Tagliatelle al Ragù Bolognese, another Bellavitae signature dish. The previous years featured Pasta alla Carbonara and Risotto alla Milanese. This year, of course, it’s Pesto Genovese.

The International Day of Italian Cuisines is born from a mission, as explained by Rosario Scarpato, GVCI Honorary President and IDIC 2011 Director:

“We certainly aim at educating worldwide consumers, but more than anything else, we want to protect their right to get what they pay for when going to eateries labeled as ‘Italian’; that is, authentic and quality Italian cuisine.”

So in celebratory spirit we again participate this year. The weather outside may be cold, but think of the following as a virtual culinary vacation to the Italian Riviera. Bookmark this page and return to it during the summer when basil is in full season. Follow the detailed recipe within and discover why Pesto Genovese has remained one of Italy’s most famous dishes.

.

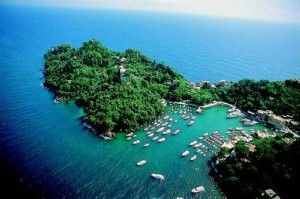

Liguria, One of the Most Beautiful Places on Earth

Pesto Genovese traces its beginnings to Genoa, the seaport city in Liguria along the famed Italian Riviera. Liguria is a narrow strip of land nestled between the Mediterranean and the Alps and Apennines mountains.

Its cuisine revolves around bountiful Mediterranean seafood; and balmy and sunny days provide the perfect environment for luscious fruits and vegetables, aromatic herbs, and fragrant olive oil. As Marcella Hazan describes it:

“Sheltered by the Apennines’ protecting slopes and bathed by soft Mediterranean breezes, Liguria enjoys the gentle weather synonymous with the Riviera. Here flowers thrive, olive groves flourish, fragrant herbs come up in every meadow and abound in every dish. It is no accident that this is the birthplace of pesto.”

The History of Pesto

The word pesto comes from pestare [to crush something with a pestle; reducing it to powder, a mash, or to the thinnest of layers]. In Italy, pesto is also known as battuto Genovese. There are many Italian cooks, when referring to any battuto, who might say they are making a pestino [a little pesto].

The recipe for pesto, like all classic dishes, has evolved – not only over a generation or two, but over centuries. Genoese pesto probably descends from the ancient Roman moretum – a green paste made from cheese, garlic and herbs, the preparation of which is described in a verse attributed to Virgil.

In the Middle Ages, there was a peasant sauce which many consider to be the predecessor of pesto. It was called agliata – simply a mash of walnuts and garlic. For centuries, garlic was an important part of Ligurian cuisine, especially for those who went to sea. Genoa and Liguria have ancient maritime traditions and seafarers ingested great quantities of garlic because they believed it warded off illnesses and infections during long voyages at sea.

.

The First Recipes

Mashed garlic is mentioned in 17th century documents of the City of Genoa, while authentic pesto recipes begin to appear in the 19th century. In 1863 Giovanni Battista Ratto published La Cuciniera Genovese [The Genoese Cook], considered to be the first and most complete book of Ligurian gastronomy and in which the recipe for pesto with pine nuts, is the following:

“Take a clove of garlic, basil (‘baxaicö’) or, when that is lacking, marjoram and parsley, grated Dutch and Parmigiano cheese and mix them with pine nuts and crush it all together in a mortar with a little butter until reduced to a paste. Then dissolve it with good and abundant oil. Lasagne and troffie [Liguriun gnocchi] are dressed with this mash, made more liquid by adding a little hot water without salt.”

The presence of Dutch cheese instead of pecorino is no surprise because many recipes of the time mention a generic cacio [cheese]. Gouda was plentiful in Genoa due to the city’s maritime commerce with Northern Europe. Parsley or marjoram were mentioned as alternatives to basil, which although was abundant, had a shorter growing season.

Ratto’s recipe for pesto stated unmistakably that it was a sauce for dressing pasta such as lasagne and trofie. Trofie are kneaded out of white flour – elongated and twisted gnocchi, with pointed extremities and fatter waists. They are a specialty of the town of Recco in the Province of Genoa – the same town that gave birth to focaccia.

By 1876, pesto was entered by Giovanni Casaccia in his Genovese Italian Dictionary.

Giuseppe Gavotti wrote in 1973 in his Cucina e Vini di Liguria [Food and Wine of Liguria], that the original pesto was “uncouth” because it contained so much garlic. Gastronomist Massimo Alberini, in his 1965 I Liguri a Tavola, Itinerario Gastronomico da Nizza a Lerici [The Ligurians at the Table, a Gastronomic Itinerary from Nice to Lerici], made a similar observation, explaining that pesto recipes of the 1800s were somewhat stingy with the basil – using only a couple of leaves – and abounding in garlic, using three or four cloves of it (Mama mia!). This was due largely to the Arab-Persian influence – which dominated the sauces of Genoa at the time — as well as Ligurian seafarers’ preference for the “medicinal” garlic. Today’s pesto is balanced, with a more noticeable presence of basil.

Giuseppe Gavotti wrote in 1973 in his Cucina e Vini di Liguria [Food and Wine of Liguria], that the original pesto was “uncouth” because it contained so much garlic. Gastronomist Massimo Alberini, in his 1965 I Liguri a Tavola, Itinerario Gastronomico da Nizza a Lerici [The Ligurians at the Table, a Gastronomic Itinerary from Nice to Lerici], made a similar observation, explaining that pesto recipes of the 1800s were somewhat stingy with the basil – using only a couple of leaves – and abounding in garlic, using three or four cloves of it (Mama mia!). This was due largely to the Arab-Persian influence – which dominated the sauces of Genoa at the time — as well as Ligurian seafarers’ preference for the “medicinal” garlic. Today’s pesto is balanced, with a more noticeable presence of basil.

.

Variations

In the 1800s, Pasta al Pesto was considered to be a working class dish and today the recipe has remained substantially the same. There also remains a tradition of adding potatoes, broad beans or French green beans, and sometimes zucchini cut into small pieces and boiled together with the pasta. Particularly in Genoa, potatoes and French green beans are added to classic or whole wheat trenette or trofiette.

As with all classic dishes, it’s difficult to find two identical versions of pesto, sometimes within the same family. For instance, there can be the addition of walnuts, ricotta, or other cheeses. In classic Italian cooking, these variations not only represent a wealth of diversity, but also an indirect legitimization of any generally accepted version.

In his 1997 book Recipes from Paradise: Life & Food on the Italian Riviera, Fred Plotkin tells of pesto throughout Liguria, and the passionate views every cook has regarding how to make it. He describes the region’s superlatively perfumed small-leafed basil, and then notes 16 versions of the famed sauce.

.

Pesto Dishes

The most popular dishes that use pesto include:

- Trofie al Pesto [Ligurian Gnocchi with Pesto]

- Mandilli de Sæa al Pesto [Silk Handkerchiefs with Pesto]

- Piccagge [Ligurian Boiled Lasagne with Ricotta Pesto]

.

The most common pastas for pesto include:

- Trenette (the classic)

- Spaghetti

- Tonnarelli

I also like pesto with potato ghocchi. In Milan, they use pesto in a summer minestrone that features Arborio rice.

.

The Ingredients

Pesto is a case study in classic Italian cuisine:

- Ingredients, few in number, but freshest available

- Perfect flavor balance

- Simple execution

- And most importantly – a celebration of the garden rather than fussiness in the kitchen.

.

The recipe is simple, the technique easily learned. The care in this dish is in the ingredients, as described below. While you may not be able to duplicate exactly the sauce as prepared in Genoa, careful selection of the ingredients and a watchful eye toward balance will ensure success.

We’ll update this article when basil is in season, touching on the following:

- Growing your own basil

- Storing basil

- Selecting and cooking with garlic

- Recipes that use pesto

.

In the meantime, here are the optimal ingredients cooks use in Genoa when making their famous pesto:

.

Basil [Baslico]

Basil [ocimum basilicum] is an herbaceous member of the mint family. It is a delicate herb, and contains more than 1% essential oil which supplies an intense, spicy-sweet aroma with a slight anise-like undertone.

In addition to its culinary use, basil has a long history as a medicinal herb. The Greek physician Dioscorides prescribed basil for a headache. Pliny thought it was an aphrodisiac; his contemporaries fed it to horses during the breeding season. In modern aromatherapy, basil is used to cheer the heart and mind. The sweet, energizing aroma is believed to help relieve sorrow and melancholy. In Italy, it is considered a sign of love — in the past, women who were ready to receive a suitor might put out a pot of basil as a sign of their willingness.

Basil is a polymorph, meaning it occurs in many different forms, varieties, and closely related species. The different types are easily hybridized, producing many kinds of plants with different essential oil compositions. There are cinnamon, lemon, clove and licorice scented basils; purple and green, curly and lettuce-leafed varieties. Dwarf bush types with tiny leaves are grown as ornamental plants.

The principal essential oils that give basil its intoxicating aroma and flavor are:

- Linalool, also found in lavender and clary sage

- Methyl Chavicol, which is found in tarragon

- Eugenol, which is found in clove and allspice

.

The classic basil used in pesto is from the small village of Prà, southwest of Genoa and is called Genovese basil (in Ligurian dialect baxaicò or baxeicò). It is a cultivar (cultivated variety) of sweet basil. This is the variety you should look for in the supermarket or when buying seeds for the garden.

Use only the freshest basil you can find, as it does not keep very well once harvested. If at all possible, grow your own! Although the plant is very sensitive after it is picked, in the garden it is very hardy. It thrives in full sun, although with partial shade you will achieve more tenderness and better flavor. Pick the plants while the leaves are still young, preferably in the morning, before the intense sunlight.

.

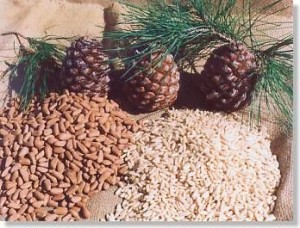

Pine Nuts [Pinoli]

In Italy, pinoli come from the Mediterranean Stone Pine (pinus pinea), which has been cultivated for its nuts over the last 6,000 years. Pinoli from wild trees have been harvested and used even longer. Janet Fletcher explains:

“The ancient Greeks and Romans also ate pine nuts. Archaeologists have found the seeds in the ruins of Pompeii. Indeed, according to Johan’s Guide to Aphrodisiacs, pine nuts were a sort of early Viagra. The Roman poet Ovid includes ‘the nuts that the sharp-leaved pine brings forth’ on a list of love potions.”

There are many varieties of pine nuts, but the two principal types are Italian and Asian. Italian pine nuts are long and slender and have a delicate nutty flavor, whereas Asian pine nuts are more rounded, more pungent, and oilier. The Italian version has the highest protein content (34%) of any species. They are much more expensive, but with the small amount used in this recipe, why not splurge a little?

Because of their high oil content, pine nuts can turn rancid quickly once they are shelled. Store in the refrigerator (up to three months) or freeze them (up to nine months).

A small portion the population can experience taste disturbances after eating pine nuts, developing 1–3 days after consumption and lasting for days or weeks. A bitter, metallic taste is described. Though very unpleasant, there are no lasting effects. Some refer to this phenomenon as “pine mouth”. If you’re one of the unfortunate few that experience this distress, you can find more information here.

By the way, the correct Italian spelling is “pinoli”, not the commonly used “pignoli”, the singular of which is actually a word used to describe a fussy, overly fastidious or extremely meticulous person). Pignoli cookies, an Italian-American specialty confection would be called biscotti ai pinoli in Italy.

.

Grated Hard Cheese

Authentic pesto is typically made with two types of grated cheese, Parmigiano-Reggiano and Pecorino. Many recipes call for only Parmigiano-Reggiano, but the addition of a smaller portion of Pecorino adds bit of sharpness and structure (through its higher protein) that provide perfect balance to the basil and garlic.

.

Parmigiano-Reggiano

It is said that Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese has been “a great cheese for at least nine centuries”— a reflection not only of its ancient origin, but the fact that this cheese is identical to how it was eight centuries ago. It has the same appearance and the same extraordinary fragrance. It’s made in the same way, in the same places, and with the same expert ritual gestures. Today, as in the past, cheese masters make Parmigiano-Reggiano with only milk, rennet, fire, and art.

There is simply no suitable American substitution for Italian Parmigiano-Reggiano. If you use anything else – and this goes for most any Italian dish – you will surely be disappointed in the result. I’m aware of a few dairies in Wisconsin that are beginning to produce parmesan cheese, but to date they have been unsuccessful in any close duplication (I’m sure with time they may come close!).

American-made parmesan cheese is pasteurized, which kills many of the important microorganisms. Italian Parmigiano-Reggiano is unpasteurized, but is aged for a minimum of 12 months, up to 24 months, rendering any dangerous bacteria harmless. Parmigiano-Reggiano, however, assumes its full and typical characteristic qualities only after a period of aging that exceeds 18 months.

Parmigiano-Reggiano is produced exclusively in the provinces of Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena and parts of the provinces of Mantua and Bologna, on the plains, hills and mountains enclosed between the Po and Reno rivers.

.

Pecorino

The word pecorino is from the Italian word for sheep, pecora. Unlike cows, sheep refuse to live in barns or even pens, finding only open fields and meadows suitable. Cows eat a steady diet of what farmers feed them all year long. Sheep, on the other hand, graze on the grass, wildflowers, and weeds indigenous to where it roams.

Milk reflects the greatest expression of terroir – what the animal eats, drinks, even the air it breathes – of any food we consume. And like wine, the unique flavors resulting from terroir are amplified as cheese ages. As any wine lover knows, you can’t duplicate terroir. This explains pecorino’s richness and depth of flavor, which is greater than any cow’s milk cheese.

Pecorino is also very seasonal in that a ewe will only part with her milk when she is not feeding a newborn, usually from fall to spring.

In Italy, cow’s milk cheeses are made from either wholly or partially skimmed milk. Pecorino is always made with whole milk. Sheep’s milk is also much higher in protein content, particularly a protein called casein, which comes from the Latin word caseus. The Roman words for cheese – cacio – and cheese maker – casaro, are derived from this word. This protein makes pecorino the cheesiest of cheeses!

Pecorino becomes a hard cheese after it has lost most of its moisture, which takes between eight months and a year. The best known is Pecorino Romano DOP, which is the oldest of all Italian cheeses – it has been made since the time before Christ. Most of this cheese was traditionally produced just outside of Rome, but nearly all the production has now been moved to Sardinia.

The majority of Pecorino Romano is made for export to North America, due largely to Italian-American cooking. The cheese is characterized by a very sharp, salty taste that is reserved for very few authentic Italian dishes. For pesto, a more subtle, supporting pecorino is Fiore Sardo [Flower of Sardinia], sometimes called Pecorino Sardo, which is what we recommend for this dish.

.

Olive Oil [Olio d’Oliva]

Ligurian olive oil is fruit-forward and delicate. It is unique in that most Ligurian producers use only a single variety of olives to produce oil, whereas other regions, such as Tuscany and Sicily, use a blend of two or more varieties. The leading variety is Taggiasca, named for the town of Taggia in the province of Imperia.

At Bellavitae, we used BuonOlio Extra Virgin Olive Oil DOP Riviera dei Fiori, made by Gigi Benza and his mother Claretta. It’s made from 100% Taggiasca olives and is the quintessence of the Italian Riviera’s olive oil. Its delicate and fruity character blends perfectly with basil. The American importer of the oil, Gustiamo, has this to say about Gigi:

“Liguria is famous for its olive oil: weather, vicinity to the sea, calcareous soil made it perfect to grow the local Taggiasca olive trees. But the olive groves are perched on terraced hills, very difficult to cultivate with modern machinery, olives must be picked by hand and the groves are progressively being abandoned by their original farmers, giving space to fires and desolate landscape. Gigi is a passionate young man with a big heart, hopes and a clear vision for his future: he wants to do good for his land and his beautiful region! A few years ago, he started to buy abandoned tree groves, reclaiming the landscape to its original magnificence. He has now 4,000 trees. We wish him good luck and more BuonOlio for Gustiamo and our friends in the future!”

We highly recommend this olive oil. You can purchase it here.

.

Garlic [Aglio]

The overuse of garlic is the single greatest error one can commit when cooking in the Italian style. Garlic typically plays a supportive role and almost always remains in the background – it should never steal the show. Garlic in pesto is no exception. Italian garlic is typically much milder than its American counterpart, especially the famed Vessalico garlic, known throughout Italy for its delicate flavor and favorable digestibility.

Among the many varieties of garlic grown in Italy, only 10% contain a red pigment, which can be divided into four sub-varieties: Rosa Napoletana, Rosa di Agrigento, Rossa di Sulmona, and Rosa di Genova. The latter is the genetic origin of the variety grown in the Arroscia Valley, in the Communes of Borghetto, Aquila, and Vessalico. Vessalico garlic, grown at an altitude above 400 meters, is famous all over Italy; the area hosts an annual garlic fair that has been held for over 300 years (generally on 2nd July).

The exceptional taste qualities of Vessalico garlic are determined by two factors: First the climate and the range of temperature variations, and the chemical composition of soil and water. The farmers’ care in growing and preserving the produce has been handed down for centuries, nearly all of it manual and organic. The garlic’s stem is kept in all its length, in order to keep feeding the bulb and preventing it from drying out. The stems are then woven into long, intricately laced braids, called reste.

Vessalico garlic is fundamental in Ligurian pesto and irreplaceable in the recipe of ajé, a mayonnaise made made with a mortar & pestle, with egg and olive oil, very much related with the French aïoli.

.

Sea Salt [Sale Marino]

The preferred salt here is Sale di Civera. Cervia’s sea salt is known for its absence of bitter minerals so it’s naturally more dolce or sweet than other sea salts. Long favored by popes, it’s also the trusted choice of many Emilia Romagna specialty producers for salting their Parmigiano-Reggiano and Prosciutto di Parma. Salt production at Cervia, a small town between Ravenna and Cesenatico on Italy’s Adriatic coast, dates back more than 2,000 years, beginning with a mixed history dealing with the Umbrans and Greeks. Its name comes from the Latin acervus meaning a mound of white salt, called “white gold.”

Sale di Cervia is entirely sea salt, with 2-4% natural humidity. It is never artificially dried or blended with anti-caking additives. This method preserves all of the minor elements found in sea water: iodine, zinc, copper, manganese, iron, magnesium and potassium. The salt workers closely monitor the entrance of concentrated salt water and as soon as sodium chloride has formed, run off the mother brine which contains the bitter chlorides. This and the muds formed are used for therapy treatments at Cervia spas.

Sale di Cervia is often refered to as Il Sale dei Papi [Pope’s Salt], as it is traditionally the seasoning sent to the Papal table. In early modern history, salt production belonged to the Bishop of Cervia and was taxed heavily. Today this sea salt is used by saints and sinners alike to season vegetables, carpaccio, roasted meats, grilled fish, salads, and more.

.

Where to Buy it

If you’re not able to find some of the ingredients needed, check Bellavitae’s online Italian Marketplace:

- Basil seeds

- Pine Nuts

- Parmigiano-Reggiano

- Fiore Sardo (Pecorino Sardo)

- BuonOlio Ligurian Extra Virgin Olive Oil

- Sale di Cervia Sea Salt

.

Equipment

The Mortar & Pestle. I used to tell our kitchen staff that the most important ingredient in pesto is elbow grease. Using a mortar & pestle is relatively easy and really takes no time at all. We would make many servings every night at the restaurant, so we utilized a large one that was carved out of Thai granite. We could make up to four servings at a time. You can find it here. I prefer the heavy models, so the heavy pestle can help do the work for you. If you’re a traditionalist, you should use a marble mortar and a wooden pestle.

The word “pestle” comes from the word pestare (pestillium in Latin, pestello in Italian) that together with the mortar is the utensil used for making pesto. The word “mortar” is derived from the Latin mortarium, a recipient in which ingredients are minced or mashed, historically not only used in kitchens but also in traditional pharmacies. Similar utensils are found throughout the world, such as the molcajete and metate of Central America and Japan’s suribachi.

While you certainly can make pesto using a food processor, it is not as preferable as the mortar & pestle method. As chef Enrico Tournier explains:

“When we prepare pesto genovese with the classic mortar and pestle, we subject the instrument to the product while respecting the right proportions of the ingredients because we are the ones to decide the proportions of the doses. While when using a mixer, in order to succeed in cutting the basil we have to add more oil than otherwise necessary, thus altering the doses and in such manner we subject the product to the instrument.”

The Proportion (for six servings)

- ½ cup extra virgin olive oil

- 50 grams tightly-packed fresh basil leaves (about 2 cups)

- 2 small garlic cloves, finely chopped (about 1½ teaspoons)

- 6 tablespoons freshly-grated Parmigiano-Reggiano (about ⅓ cup)

- 2 tablespoons freshly-grated Fiore Sardo (if using Pecorino Romano, use 1 tablespoons and 7 tablespoons Parmigiano-Reggiano)

- 1 tablespoon lightly-toasted pine nuts

- Coarse sea salt

.

Making Pesto

- Soak the basil leaves in cold water, and then pat them gently but thoroughly with towels.

- Put the coarse salt and garlic into the mortar.

- Add about a third of the fresh basil leaves and begin to grind the ingredients with the pestle, using a rotary movement.

- After the basil begins to break down, add another third of the leaves.

- Add the final third of the leaves, continuing to grind them into a paste.

- Add the pine nuts and grind them in with the pestle, which will begin to amalgamate and soften the sauce.

- Add the grated cheeses and use the pestle to incorporate completely.

- Add the olive oil, slowly in a thin stream, and stir with a wooden spoon until distributed evenly.

- Serve immediately

.

Tips for Success:

- Most of basil’s essential oils are stored in the veins of its leaves, so to get the best taste, don’t pound the leaves, but slightly rotate the pestle to rip the fragrant leaves.

- Processing should take place at room temperature and should end as soon as possible to avoid oxidation.

.

Wine Pairings for Pesto Genovese:

These are some of the wines we like to drink with Pesto Genovese. Click on the links for more information or to purchase them from wine.com:

Arneis

Chardonnay

Pinot Grigio

J. Hofstatter 2009 Alto Adige Pinot Grigio

Further Reading:

- The Official Dish of the IDIC 2011: Pesto Genovese

- Consorzio del Pesto Genovese: The Official Recipe

- Fred Plotkin: Recipes from Paradise: Life & Food on the Italian Riviera

- Rose Levy Beranbaum: Pesto Perfect

- gustiBlog: Buonolio from Liguria, 100% Taggiasca and Do Good for Liguria

- Thomas Debaggio and Susan Belsinger: Basil: An Herb Lover’s Guide

- Janet Fletcher: Pine Nuts – The Popularity of Pignoli

- Parmigiano-Reggiano Cheese Consortium

- Sardegna Agricoltura: Pecorino Sardo DOP

- Seeds from Italy: Genovese Basil

- ItalyTraveller: The First Salt of Summer

- Genoa’s Basil Park: Il Parco del Basilico di Genoa Prà

- Laura Schenone: Visiting Liguria

- Official Tourism Site: Liguria Region

.

3 thoughts on “Ricette Classiche: Pesto Genovese”